For the past four weeks I've been fixated on the concept of grouping notes together. To sum up, this is important for both the learning process and for the understanding and communication of music. You've got to take a breath somewhere! but....

Grouping is not the same as phrasing. Groups of notes are usually in smaller packages than phrases, and function more like words or phrases in English than sentences, which might be the equivalent of a musical phrase. They are smaller units. And one doesn't necessarily "breathe" after each group. However...

One needs to be able to breathe mentally. That is, you have to make a mental break between those groups, understanding them as separate units of music. Within those groups, however, it is important not to make breaks.

Here is something from a recording I made yesterday...

listen

Notice how the last three chords sound like one group. They even feel like one group, with a forward momentum that carries them through with one gesture. While my fingers have to play and release, moving up and down three times, my arm is moving forward only once, unifying the disparate motions of my fingers so that to me this entire grouping feels like one motion--toward the piano. This is the physical, technical side of grouping. The audience hears this as well, which makes aural interpretation much easier, since the mountain of material has already been sorted and grouped. It also makes it, in this case, more exciting to listen to, because the contents seem alive. Now I'll play you the whole passage. The musical selection itself will come next week!

listen

Finally, being able to group is an invaluable aid in the learning process. I can remember a 7-digit phone number much more easily if I group it into chunks of 3 and 4 digits. And while a seven digit number has been shown to be a limit for our immediate memory, there are no such limits for our long term capacity, however "Whereas a chain of letters like CBSMTVIRSSUVTNT might be difficult for labile memory to hang onto, once the letters are chunked into CBS-MTV-IRS-SUV-TNT, the task becomes much easier, and what would never have made it into stable memory has a greater chance of consolidating." point out four brilliant authors of "Individual and Collective Memory Consolidation" Anastasio, Ehrenberger, Watson, Zhang, 2012). Full disclosure: one of these brilliant authors is Mrs. Pianonoise.

In the example above, it turns out that chunking the information into 3-digit pieces produces recognizable acronyms. However, in musical interpretation, different players may come to quite different results. (How about if I group them so they all rhyme? CB-SMT-VIRSSUV-TNT! works as a cheer--has a nice chanting rhythm to it--and as a young person I may not recognize CBS anyhow!) Generally, however, the chunks are fairly short, sometimes they overlap (thus the final note of one may also be the beginning of the other) and they can often be found because of some relation they have with the preceding or succeeding material (such as a pure repetition, a sequence, some kind of development, or the start of a new chain of similar cells). Chunking is fun, chunking is a necessity, it is a way of life. It brings order to disparate elements, and ease of understanding. It separates professionals from amateurs, skilled interpreters from people who are just playing notes and don't sound like they know what they are musically "talking" about.

It is strange people didn't spend time talking about this at the conservatory. Still, you can hear an element of this in the practice room, as people take small bits of pieces and play them over and over in order to acquaint their fingers, wrists and arms with their routes. If the mind is engaged in the process, all the better. And all the difference.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Monday, October 28, 2013

Who really wrote the 8 little preludes and fugues? (part two)

Last week I said I would furnish some support for my contention that J. S. Bach did not write the "8 little preludes and fugues" that were (or are) sometimes attributed to him. This plan of action is none too popular with some musicians, I've noticed. Whenever scholars make some sort of pronouncement about the authenticity of pieces of music, some folks like to simply roll their eyes and mutter under their breath. I think it shows more maturity and intellectual growth to read the arguments and consider what they've said rather than stubbornly cling to whatever we'd like to be right without informing ourselves of what they've said.

At the moment, however, I haven't read any of the literature yet, either, and I don't expect to get a chance in the very near future. I am, instead, offering my own thoughts on the matter, and, later, I can find out whether some of the people who have written scholarly articles on the subject have come to the same conclusions I have, or have things I haven't yet considered, or both.

As I wrote last week, part of the issue seems tied to the question of quality. If you think highly of these works you want them to have been written by Bach, particularly if you are an amateur organist, because these pieces are much easier to play than practically everything else that we can certainly attribute to Bach, and that way you can feel you are playing something by the great J. S. On the other hand, if you don't think much of these pieces, you might be willing to suggest, or even want to suggest, that someone else wrote the pieces. A large part of my argument today is the point out flaws in the compositions, to unpack what someone might mean when they suggest that the pieces are not of high quality. If you disagree, you may need a strong stomach for this one. I'm sorry to poke holes in your musical favorites, although I will say that growing as a musician often requires reassessing our most cherished opinions, and questioning what we know.

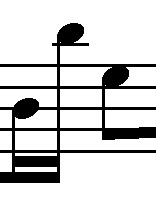

There is the matter of counterpoint. These pieces do not contain any parallel fifths or octaves that I can think of; however, there is often weak counterpoint nonetheless. For example, the opening of the G major prelude contains this passage in which the tenor voice gives out an A to G, and this is followed immediately by the alto voice, also with an A to G. The octaves are staggered: they do not occur at the same time. But they still sound like the independence of the two voices has been compromised, which is what is at the heart of the prohibition of parallel octaves and fifth. The counterpoint is less full and less rich because of it.

listen

When you listen to it it actually sounds like the same voice repeating itself because with various stops drawn each note is sounding at its own octave and the octave above, so it is harder to distinguish between the voices. This counterpoint doesn't help that any. It is not an example of a technical "theory class" infraction, but it is weak writing nevertheless.

Something that occurs toward the end of the same prelude is a very short dominant pedal point. This, to me, seems very abrupt, and I have a hard time believing that Bach, who was able to stretch such periods of tension before the final release to incredible lengths at times, would write a dominant pedal that has barely begun before it is over.

listen

These are two different kinds of defects, one related to the quality of the counterpoint, another to the handling of compositional structure. There are many places where the harmony is left incomplete so that one voice may double something that is in another voice, unnecessarily. I would list them but I seem to have left my scores on the organ. Can you trust me?

There are, of course, places in the same pieces where the counterpoint is stronger, and also where the structure is not so perfunctory. I am reminded of a long pedal point at the end of the A minor fugue, which, together with its prelude, is currently my favorite of the set, and may well be the best, from a compositional point of view as well. It also brings up the possibility that not all 8 necessarily came from the same source. Could Bach have written some but not others? Although I still am not sure I would assign the A minor prelude to Bach, it might be first in line if I changed my mind.

A large part of a musicologist's argument often tracks not whether the ideas a composer has are any good but what the composer does with them. This is often the difference between composers of genius and those who simply aren't half bad. Whether this kind of argument takes hold in you or not will depend on your ability to appreciate the working out of ideas rather than to just enjoy the presentation of the ideas themselves. I will state baldly that I have gone from one side to the other as I have grown in my musical ability, and so, I imagine, would anyone else. In other words, it takes a more developed person to appreciate arguments, whether in words or in music, that are well developed, and not simply to enjoy the tang of a catchy musical idea which is repeated many times with little development, as happens in most popular music.

For instance, as ebullient as the C major prelude is, the sequence of chords that follow the opening measures and get us into the new key are only impressive if you haven't heard them from any number of other sources (Vivaldi himself has given us several hundred examples!). It is a very quick and efficient way of getting us to G major, which is the necessary structural point of this sort of composition, but the chords, which, by the way, would furnish a simple example for a theory class learning secondary dominants to label for homework, don't go outside of this Baroque/classical cliche. It's pretty, says Kipling's devil, but is it art?

listen

One thing that those ready-made sequences suggest (other than that he could have gotten them from IKEA) is that this composer was not in command of a rich, abundant harmonic palette. Just as Shakespeare had an enormous vocabulary of over 600,000 words (many of which he created himself), Bach usually does quite a bit more than hand us a chord progression that could have been written by just about any composer, and not do anything unique with it. And that is the point: it is present here at the start of the F major prelude as well:

listen

It sounds to me as if part of the spirit of these pieces belong really to the generation after Bach, when simple harmonic outlines, short and elegant phrases, and less contrapuntal involvement were on the rise. It was a simpler time. Could that thought point us in the direction of who might have actually written the pieces? The two questions are related, though it should not be necessary for us to be certain who DID write the pieces even if we feel that Bach did not. Krebs, after all, was a student of Bach's, and much younger. Our scant Wikipedia research suggests he was stylistically attached to Bach and that his counterpoint was thought to be almost as good. All I can say to that at present is hmmm. I don't really buy it.

But the hour is growing late, and I have more rehearsals to run off to. Shall we carry this discussion over 'till next Monday?

At the moment, however, I haven't read any of the literature yet, either, and I don't expect to get a chance in the very near future. I am, instead, offering my own thoughts on the matter, and, later, I can find out whether some of the people who have written scholarly articles on the subject have come to the same conclusions I have, or have things I haven't yet considered, or both.

As I wrote last week, part of the issue seems tied to the question of quality. If you think highly of these works you want them to have been written by Bach, particularly if you are an amateur organist, because these pieces are much easier to play than practically everything else that we can certainly attribute to Bach, and that way you can feel you are playing something by the great J. S. On the other hand, if you don't think much of these pieces, you might be willing to suggest, or even want to suggest, that someone else wrote the pieces. A large part of my argument today is the point out flaws in the compositions, to unpack what someone might mean when they suggest that the pieces are not of high quality. If you disagree, you may need a strong stomach for this one. I'm sorry to poke holes in your musical favorites, although I will say that growing as a musician often requires reassessing our most cherished opinions, and questioning what we know.

There is the matter of counterpoint. These pieces do not contain any parallel fifths or octaves that I can think of; however, there is often weak counterpoint nonetheless. For example, the opening of the G major prelude contains this passage in which the tenor voice gives out an A to G, and this is followed immediately by the alto voice, also with an A to G. The octaves are staggered: they do not occur at the same time. But they still sound like the independence of the two voices has been compromised, which is what is at the heart of the prohibition of parallel octaves and fifth. The counterpoint is less full and less rich because of it.

listen

When you listen to it it actually sounds like the same voice repeating itself because with various stops drawn each note is sounding at its own octave and the octave above, so it is harder to distinguish between the voices. This counterpoint doesn't help that any. It is not an example of a technical "theory class" infraction, but it is weak writing nevertheless.

Something that occurs toward the end of the same prelude is a very short dominant pedal point. This, to me, seems very abrupt, and I have a hard time believing that Bach, who was able to stretch such periods of tension before the final release to incredible lengths at times, would write a dominant pedal that has barely begun before it is over.

listen

These are two different kinds of defects, one related to the quality of the counterpoint, another to the handling of compositional structure. There are many places where the harmony is left incomplete so that one voice may double something that is in another voice, unnecessarily. I would list them but I seem to have left my scores on the organ. Can you trust me?

There are, of course, places in the same pieces where the counterpoint is stronger, and also where the structure is not so perfunctory. I am reminded of a long pedal point at the end of the A minor fugue, which, together with its prelude, is currently my favorite of the set, and may well be the best, from a compositional point of view as well. It also brings up the possibility that not all 8 necessarily came from the same source. Could Bach have written some but not others? Although I still am not sure I would assign the A minor prelude to Bach, it might be first in line if I changed my mind.

A large part of a musicologist's argument often tracks not whether the ideas a composer has are any good but what the composer does with them. This is often the difference between composers of genius and those who simply aren't half bad. Whether this kind of argument takes hold in you or not will depend on your ability to appreciate the working out of ideas rather than to just enjoy the presentation of the ideas themselves. I will state baldly that I have gone from one side to the other as I have grown in my musical ability, and so, I imagine, would anyone else. In other words, it takes a more developed person to appreciate arguments, whether in words or in music, that are well developed, and not simply to enjoy the tang of a catchy musical idea which is repeated many times with little development, as happens in most popular music.

For instance, as ebullient as the C major prelude is, the sequence of chords that follow the opening measures and get us into the new key are only impressive if you haven't heard them from any number of other sources (Vivaldi himself has given us several hundred examples!). It is a very quick and efficient way of getting us to G major, which is the necessary structural point of this sort of composition, but the chords, which, by the way, would furnish a simple example for a theory class learning secondary dominants to label for homework, don't go outside of this Baroque/classical cliche. It's pretty, says Kipling's devil, but is it art?

listen

One thing that those ready-made sequences suggest (other than that he could have gotten them from IKEA) is that this composer was not in command of a rich, abundant harmonic palette. Just as Shakespeare had an enormous vocabulary of over 600,000 words (many of which he created himself), Bach usually does quite a bit more than hand us a chord progression that could have been written by just about any composer, and not do anything unique with it. And that is the point: it is present here at the start of the F major prelude as well:

listen

It sounds to me as if part of the spirit of these pieces belong really to the generation after Bach, when simple harmonic outlines, short and elegant phrases, and less contrapuntal involvement were on the rise. It was a simpler time. Could that thought point us in the direction of who might have actually written the pieces? The two questions are related, though it should not be necessary for us to be certain who DID write the pieces even if we feel that Bach did not. Krebs, after all, was a student of Bach's, and much younger. Our scant Wikipedia research suggests he was stylistically attached to Bach and that his counterpoint was thought to be almost as good. All I can say to that at present is hmmm. I don't really buy it.

But the hour is growing late, and I have more rehearsals to run off to. Shall we carry this discussion over 'till next Monday?

Friday, October 25, 2013

Thinking warm thoughts

How many of you know Edith Bunker?

She's a character from a 1970s television sitcom called "All in the Family." Unlike her argumentative, bigoted husband Archie, Edith was the nicest person you could ever meet and everybody just loved her. But she was a little...odd, sometimes.

In one episode, the family is looking at old photographs, and she observes that she always wonders what happened to the people in the picture right after the picture was taken. One moment, there they are, still for the camera, the part we have on record, and then, they must have all started to move, but where? The camera didn't capture that part. The family just look at her like she's gone nuts.

I have a little bit of Edith in me. Sorry, did I type that out loud? Don't tell anybody.

A week ago today the folks from the heating and cooling service came to our church and inspected the furnace and basically switched everything over from air conditioning to heat. We are now, officially, in the cold and dark part of the year. And it got me thinking about organ music. For some reason, listening to some of the music I've played in past years seems to warm me up. Probably because it reminds me of precisely that time of the year when the world outside is cold and the sanctuary is (moderately) warm, and, especially at Christmas, there is musical cheer to be had as we survive and thrive our way through the season.

That's not really all that weird, is it? People tend often to have memories associated with pieces of music. I just happen to have a lot of other layers to put on top of them. But there are still pieces of music that I associate with certain seasons of the year, probably because that's when I first learned them. Some pieces remind me of autumn, some of spring, and many of winter. Such associations may or may not have anything to do with the music, or any kind of rationale. They might not even be conscious. I have occasionally found that if I have to put away a composition in progress because of other demands that I sometimes reflexively begin working on it again at the same time the following year.

As I said, that isn't all that rational. But then, human beings are not that rational, and living on this constantly warming and constantly cooling planet isn't that rational. If you live in the temperate zone north of the equator, this time of year the planet is cooling off pretty fast. This week, in fact, the morning low has been below freezing. And the sun won't stay out past 6:30 anymore, to say nothing of what will happen in a week when daylight saving time goes away.

That can be a bit of an inconvenience, and eventually it will probably be a psychological downer as well, but for our ancestors, too much darkness and coldness had consequences. It could inspire fear with good reason. You could really feel that chill in your bones and know what you were in for: the long siege that was winter. Time to go find a cave to keep warm. My cave just happens to be a church sanctuary. And while I'm in there, I like to make loud sounds by depressing plastic levers attached to great metal pipes with air blowing through. Makes sense, right?

That's not what keeps me warm, though. The heat keeps me warm. At a former church I used to wear a thick jacket when I practiced because the sanctuary was ice during the week. Odd, this organ music keeping me warm thing, isn't it?

21st century Americans have frequently gotten away from the elements and a sense of being part of the ecosystem. We need holidays to remind us. Our ancestors celebrated the harvest because being able to eat was kind of important. These days it's just an excuse to watch more football. And they celebrated--or at least marked--the transitions of the seasons. The air getting colder, darkness settling across the land, an excellent time to confront our fears: the big ones. Fear of death, fear of bodily harm, fear of the unknown. When the church came to town it learned that this was too big a holiday to simply wipe out, so, like Christmas, the church simply wrote over top of an existing holiday. It tried to introduce doctrinal reasons for why we celebrate them. The rational mind finds this very inviting. But the irrational part of us still celebrates the chill in the bones, the loss of the sun, the return of spring. It's an important part of us, doctrine or no doctrine.

And it's that way with music. You can learn it, you can study it, you can make erudite comments about it, but those gut level associations are still there, grinning at us, nonsensical as they are.

So if you need to stay warm this winter, there's a healthy supply of pipe organ music over at pianonoise.com. And to my friends in Australia, where things are just starting to heat up, if you need to keep cool the next few months, just listen to some of the piano music instead.

Don't ask.

She's a character from a 1970s television sitcom called "All in the Family." Unlike her argumentative, bigoted husband Archie, Edith was the nicest person you could ever meet and everybody just loved her. But she was a little...odd, sometimes.

In one episode, the family is looking at old photographs, and she observes that she always wonders what happened to the people in the picture right after the picture was taken. One moment, there they are, still for the camera, the part we have on record, and then, they must have all started to move, but where? The camera didn't capture that part. The family just look at her like she's gone nuts.

I have a little bit of Edith in me. Sorry, did I type that out loud? Don't tell anybody.

A week ago today the folks from the heating and cooling service came to our church and inspected the furnace and basically switched everything over from air conditioning to heat. We are now, officially, in the cold and dark part of the year. And it got me thinking about organ music. For some reason, listening to some of the music I've played in past years seems to warm me up. Probably because it reminds me of precisely that time of the year when the world outside is cold and the sanctuary is (moderately) warm, and, especially at Christmas, there is musical cheer to be had as we survive and thrive our way through the season.

That's not really all that weird, is it? People tend often to have memories associated with pieces of music. I just happen to have a lot of other layers to put on top of them. But there are still pieces of music that I associate with certain seasons of the year, probably because that's when I first learned them. Some pieces remind me of autumn, some of spring, and many of winter. Such associations may or may not have anything to do with the music, or any kind of rationale. They might not even be conscious. I have occasionally found that if I have to put away a composition in progress because of other demands that I sometimes reflexively begin working on it again at the same time the following year.

As I said, that isn't all that rational. But then, human beings are not that rational, and living on this constantly warming and constantly cooling planet isn't that rational. If you live in the temperate zone north of the equator, this time of year the planet is cooling off pretty fast. This week, in fact, the morning low has been below freezing. And the sun won't stay out past 6:30 anymore, to say nothing of what will happen in a week when daylight saving time goes away.

That can be a bit of an inconvenience, and eventually it will probably be a psychological downer as well, but for our ancestors, too much darkness and coldness had consequences. It could inspire fear with good reason. You could really feel that chill in your bones and know what you were in for: the long siege that was winter. Time to go find a cave to keep warm. My cave just happens to be a church sanctuary. And while I'm in there, I like to make loud sounds by depressing plastic levers attached to great metal pipes with air blowing through. Makes sense, right?

That's not what keeps me warm, though. The heat keeps me warm. At a former church I used to wear a thick jacket when I practiced because the sanctuary was ice during the week. Odd, this organ music keeping me warm thing, isn't it?

21st century Americans have frequently gotten away from the elements and a sense of being part of the ecosystem. We need holidays to remind us. Our ancestors celebrated the harvest because being able to eat was kind of important. These days it's just an excuse to watch more football. And they celebrated--or at least marked--the transitions of the seasons. The air getting colder, darkness settling across the land, an excellent time to confront our fears: the big ones. Fear of death, fear of bodily harm, fear of the unknown. When the church came to town it learned that this was too big a holiday to simply wipe out, so, like Christmas, the church simply wrote over top of an existing holiday. It tried to introduce doctrinal reasons for why we celebrate them. The rational mind finds this very inviting. But the irrational part of us still celebrates the chill in the bones, the loss of the sun, the return of spring. It's an important part of us, doctrine or no doctrine.

And it's that way with music. You can learn it, you can study it, you can make erudite comments about it, but those gut level associations are still there, grinning at us, nonsensical as they are.

So if you need to stay warm this winter, there's a healthy supply of pipe organ music over at pianonoise.com. And to my friends in Australia, where things are just starting to heat up, if you need to keep cool the next few months, just listen to some of the piano music instead.

Don't ask.

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

You have my sympathy

Sometimes, before I gave a new student his or her first piano lesson, I would get up from the bench and look at the keyboard this way:

That wasn't just to get a different perspective. It was because from that angle the keys dissolved into an ocean of identical looking plastic levers, an endless horizon of black and white. Viewed from the normal direction I cannot help feeling that each key is different from its neighbor--I don't just see keys anymore, I see a cotillion of individual keys, each of which somehow looks different from the others. It is as if all the Cs are a different color than the Ds and the Es. I am instantly at home and instantly know how to find my way around. A new student, of course, does not, and it is good to remind oneself of what that must feel like every now and then, and to be intrigued by the possibilities, as well as a little daunted by the unfamiliarity. It is an exercise in disorientation.

There is more than one way to achieve such disorientation, however. Last week I started work on a contemporary sonata for trumpet and organ. The concert is under just under a month as I write this, so I basically tried to come to terms with the entire 28-page expanse in four days. It was an experience.

The reason I am writing about it is that, for the last three weeks on the Wednesday portion of this blog we've been talking about the importance of seeing music--of understanding music--in groupings, in whole words and phrases, as both an aid to interpretation, and as an aid to learning. First I offered an apologia for why this is very necessary, and then some brief examples on how one goes about doing it. It has become instinctive for me, but it is noticeably not that way for many of us, and when it isn't, the playing suffers by at the least being uninteresting, and in some cases, rather incompetent. (The first three parts of the series are here, here, and here.)

Having offered advice, which, depending on your skill level, might either seem self-evident, revelatory, or daunting, I'm going to take a detour from the practice of finding such patterns in the music to offer some personal experience with the musical equivalent of flying blind. This is because the internet offers such a large and completely unsorted audience, from all kinds of backgrounds, which means that there is always the possibility that, in the midst of what I hope will be helpful hints toward the furtherance of an individual's journey, what will happen instead will be some head shaking and the phrase "easy for you to say." In other words, I've built up a lot of different skills over time and they work together well to allow all manner of playing difficult music in fairly large volumes, and the human tendency to expect such results without the same work over the same length of time might lead to a good deal of frustration and the sense that what I am saying is not particularly relevant to you. In such a case, consider this a bit of empathy.

One of the things that makes it easier for me to learn a piece of music is the ability to understand what musical materials the composer is using. Information like the key signature isn't just a fact to be known, it tells me what to expect in the piece to come in terms of the feel of the key's hills and valleys, or the rise and fall of the melodic patterns. If I can see what harmonies are present in each measure, I can even fake parts of it if I don't get the page turned in time, or my sight reading skills fail to provide me with all the detailed information in time. I can paraphrase if I forget something while I'm playing from memory. But my memory is in turn strengthened by the ability to hear the piece in my head and to be able to reconstruct it from the recording that is playing in my head--in other words, I can play by ear while I'm playing my sight (reading the notes in front of me) or playing from memory. And I improvise, which means I can fill in any information that fails to come by those means by simply making it up until the crisis is safely past. This sort of redundancy is like having four engines on a plane making a transatlantic flight. If one fails, you still have three to fly with. If two fail, you still have two left. Vastly different musical skills compliment each other.

But consider the problem of learning a largely a-tonal composition in a few days. There are no predictable scale or chord patterns in such a piece. Instead, the composer seems to like to play a D major chord in one hand with an F natural in the other. Or a G# will be present in the right hand, with a G natural in the other, and a G-flat in the feet. Such discords cause two problems:

One is that I have been training my hands and feet to "think" in traditional harmonic patterns and they instinctively avoid notes that are dissonant. The advantage is that even when I'm totally guessing at notes because my brain isn't working fast enough to properly read everything I'll still fill in with something that sounds harmonically acceptable. That is a large part of the reason some people think I don't miss any notes. I miss more than they might think, but most of them don't even sound bad. It's a nice habit to have built up over time, but in this case I have to virtually rewire myself to be able to play what is in the music.

The other is that wrong notes don't sound any more wrong than the right ones, which means it takes longer to figure out whether I'm playing the right notes since I can't hear them right away. It took me several days to be able to tell when I was playing wrong notes. This was an advance--even though I was still making errors in practice, at least I could tell! I'm not used to having to wait several days for this to happen. Granted, if I could "sight read the shit off fly paper" as one colleague memorably said about another when I was in grad school, I might not need to rely on those other skills as much. In this case, pattern recognition is, at first, getting in the way. Until I learn the new patterns.

The long and short of this is that I basically had to play each musical gesture a large number of times in order to "get it under my fingers." The principle way this occurs when your ear is not able to help you "hear" each gesture is by feel. You hands have to memorize the feel of each chord, its special topography. This is a slower way to learn, but it eventually works. I still recall the summer I spent before my junior year of college trying to learn a Scriabin sonata entirely by memorizing the feel of each chord, each gesture. The harmonies were at the time way beyond my comprehension: I could only come to terms with the piece by sheer repetition. Even at the recital I was frightened of the piece and was playing it with the sense that I could only get through it by remembering each detail from force of habit. These days I would understand and recognize the patterns used in the piece and would be able to breathe much more easily, and to even paraphrase if I got lost (which, in turn, makes it less likely that you will get lost in the first place--funny how that works).

Muscle memory is an important way to learn, but I find it works much better if it is accompanied by the ear being able to recognize each musical element by the sound of it. That way, when you are away from the piano or organ, you can perform the piece with your ears closed by both seeing yourself perform it, feeling the keys beneath your fingers, and hearing the sounds. If all three of those things are in working order, you are ready to play the piece. Not to mention you can still get in practice time on an airplane.

Not being able to do all of these things, or to integrate the various skills, makes learning that much harder. I got a reminder of that last week when I began work on the sonata. It was like doing a bit of time traveling, back to a time when those skills were less developed, my musical understanding much less keen. This was in college, mind you. Every year since I've graduated I've improved in some direction. Working hard and working smart will do that. But suddenly, a different sort of musical experience will throw one back on his heels, and some of your assets actually become liabilities, or are at least canceled out. It can be frustrating. And even that can be helpful in its own perverse way.

First, it helps to refine my empathy skills, and to be able to say to musicians who have not developed either their ear-training/hearing/playing by ear skills or their sight-read like heck skills or their instantly memorize anything I come across skills, I understand. It's a long process, and a difficult road at times. But the more you are able to do these things the more time you will save in the long run and the more time you will have to actually make music and enjoy life because you will spend less time being tripped up by the mechanics.

So let's say I've come back from the future to warn you. The time is now. It is always now. Do what you can to shore up you weaknesses, even a little at a time, because they will come back to haunt you. They always do. Bwahahahaha!

Happy Halloween.

That wasn't just to get a different perspective. It was because from that angle the keys dissolved into an ocean of identical looking plastic levers, an endless horizon of black and white. Viewed from the normal direction I cannot help feeling that each key is different from its neighbor--I don't just see keys anymore, I see a cotillion of individual keys, each of which somehow looks different from the others. It is as if all the Cs are a different color than the Ds and the Es. I am instantly at home and instantly know how to find my way around. A new student, of course, does not, and it is good to remind oneself of what that must feel like every now and then, and to be intrigued by the possibilities, as well as a little daunted by the unfamiliarity. It is an exercise in disorientation.

There is more than one way to achieve such disorientation, however. Last week I started work on a contemporary sonata for trumpet and organ. The concert is under just under a month as I write this, so I basically tried to come to terms with the entire 28-page expanse in four days. It was an experience.

The reason I am writing about it is that, for the last three weeks on the Wednesday portion of this blog we've been talking about the importance of seeing music--of understanding music--in groupings, in whole words and phrases, as both an aid to interpretation, and as an aid to learning. First I offered an apologia for why this is very necessary, and then some brief examples on how one goes about doing it. It has become instinctive for me, but it is noticeably not that way for many of us, and when it isn't, the playing suffers by at the least being uninteresting, and in some cases, rather incompetent. (The first three parts of the series are here, here, and here.)

Having offered advice, which, depending on your skill level, might either seem self-evident, revelatory, or daunting, I'm going to take a detour from the practice of finding such patterns in the music to offer some personal experience with the musical equivalent of flying blind. This is because the internet offers such a large and completely unsorted audience, from all kinds of backgrounds, which means that there is always the possibility that, in the midst of what I hope will be helpful hints toward the furtherance of an individual's journey, what will happen instead will be some head shaking and the phrase "easy for you to say." In other words, I've built up a lot of different skills over time and they work together well to allow all manner of playing difficult music in fairly large volumes, and the human tendency to expect such results without the same work over the same length of time might lead to a good deal of frustration and the sense that what I am saying is not particularly relevant to you. In such a case, consider this a bit of empathy.

One of the things that makes it easier for me to learn a piece of music is the ability to understand what musical materials the composer is using. Information like the key signature isn't just a fact to be known, it tells me what to expect in the piece to come in terms of the feel of the key's hills and valleys, or the rise and fall of the melodic patterns. If I can see what harmonies are present in each measure, I can even fake parts of it if I don't get the page turned in time, or my sight reading skills fail to provide me with all the detailed information in time. I can paraphrase if I forget something while I'm playing from memory. But my memory is in turn strengthened by the ability to hear the piece in my head and to be able to reconstruct it from the recording that is playing in my head--in other words, I can play by ear while I'm playing my sight (reading the notes in front of me) or playing from memory. And I improvise, which means I can fill in any information that fails to come by those means by simply making it up until the crisis is safely past. This sort of redundancy is like having four engines on a plane making a transatlantic flight. If one fails, you still have three to fly with. If two fail, you still have two left. Vastly different musical skills compliment each other.

But consider the problem of learning a largely a-tonal composition in a few days. There are no predictable scale or chord patterns in such a piece. Instead, the composer seems to like to play a D major chord in one hand with an F natural in the other. Or a G# will be present in the right hand, with a G natural in the other, and a G-flat in the feet. Such discords cause two problems:

One is that I have been training my hands and feet to "think" in traditional harmonic patterns and they instinctively avoid notes that are dissonant. The advantage is that even when I'm totally guessing at notes because my brain isn't working fast enough to properly read everything I'll still fill in with something that sounds harmonically acceptable. That is a large part of the reason some people think I don't miss any notes. I miss more than they might think, but most of them don't even sound bad. It's a nice habit to have built up over time, but in this case I have to virtually rewire myself to be able to play what is in the music.

The other is that wrong notes don't sound any more wrong than the right ones, which means it takes longer to figure out whether I'm playing the right notes since I can't hear them right away. It took me several days to be able to tell when I was playing wrong notes. This was an advance--even though I was still making errors in practice, at least I could tell! I'm not used to having to wait several days for this to happen. Granted, if I could "sight read the shit off fly paper" as one colleague memorably said about another when I was in grad school, I might not need to rely on those other skills as much. In this case, pattern recognition is, at first, getting in the way. Until I learn the new patterns.

The long and short of this is that I basically had to play each musical gesture a large number of times in order to "get it under my fingers." The principle way this occurs when your ear is not able to help you "hear" each gesture is by feel. You hands have to memorize the feel of each chord, its special topography. This is a slower way to learn, but it eventually works. I still recall the summer I spent before my junior year of college trying to learn a Scriabin sonata entirely by memorizing the feel of each chord, each gesture. The harmonies were at the time way beyond my comprehension: I could only come to terms with the piece by sheer repetition. Even at the recital I was frightened of the piece and was playing it with the sense that I could only get through it by remembering each detail from force of habit. These days I would understand and recognize the patterns used in the piece and would be able to breathe much more easily, and to even paraphrase if I got lost (which, in turn, makes it less likely that you will get lost in the first place--funny how that works).

Muscle memory is an important way to learn, but I find it works much better if it is accompanied by the ear being able to recognize each musical element by the sound of it. That way, when you are away from the piano or organ, you can perform the piece with your ears closed by both seeing yourself perform it, feeling the keys beneath your fingers, and hearing the sounds. If all three of those things are in working order, you are ready to play the piece. Not to mention you can still get in practice time on an airplane.

Not being able to do all of these things, or to integrate the various skills, makes learning that much harder. I got a reminder of that last week when I began work on the sonata. It was like doing a bit of time traveling, back to a time when those skills were less developed, my musical understanding much less keen. This was in college, mind you. Every year since I've graduated I've improved in some direction. Working hard and working smart will do that. But suddenly, a different sort of musical experience will throw one back on his heels, and some of your assets actually become liabilities, or are at least canceled out. It can be frustrating. And even that can be helpful in its own perverse way.

First, it helps to refine my empathy skills, and to be able to say to musicians who have not developed either their ear-training/hearing/playing by ear skills or their sight-read like heck skills or their instantly memorize anything I come across skills, I understand. It's a long process, and a difficult road at times. But the more you are able to do these things the more time you will save in the long run and the more time you will have to actually make music and enjoy life because you will spend less time being tripped up by the mechanics.

So let's say I've come back from the future to warn you. The time is now. It is always now. Do what you can to shore up you weaknesses, even a little at a time, because they will come back to haunt you. They always do. Bwahahahaha!

Happy Halloween.

Monday, October 21, 2013

Who really wrote the 8 short preludes and fugues?

I've been having an interesting stroll down memory lane this month. Something fellow blogger Vidas Pinkevicius wrote about the 300th anniversary of the birth of Johann Ludwig Krebs this month started a little investigation into the man's work because I'm a curious person who hadn't played any of his music before and I thought: why not play some of his music this month in church? The pastors are talking about stewardship, anyhow, which doesn't, so far as I know, lend itself to a lot of great organ music.

In the process, I wound up revisiting the "8 short preludes and fugues;" pieces that I hadn't played since I was a teenager, and then probably not well, and certainly not all of them, preludes and fugues together. I've gotten a whole lot more disciplined since then, with a better technical arsenal, and more time to spend at the organ as well. So it feels like at last I'm finishing something I started almost three decades ago, long before I learned to play the major Bach works of the past several years.

But this also brings with it a musicological question. Who wrote these pieces? When I first encountered them, at the age of 13, they were attributed (in my book) to J. S. Bach. I didn't know Bach's style very well, so I just went along with it. It was in a book, after all, so they must be right! Since then, I've changed my mind. Which is why, this weekend at church I'll play two of the pieces as part of my three week birthday celebration of Mr. Krebs. It would be a shame if I was celebrated the man's birthday with music he didn't actually write. But I'm pretty confident in my attribution.

Once I heard about the controversy, though, I wanted to find out about it. I'm pretty short on time these days, however, so all I've managed to do so far is go to Wikipedia. The article there was pretty biased in favor of Mr. Bach being the author. Why do I say that? Because all they will tell me is that there "used to be" "some" who thought that Krebs was the composer. Notice they don't name anybody. But now, they say, Bach is again thought to be the composer, and this time they list three scholars who are inclined to that opinion. [update: the article has undergone significant editing since this blog was written]

The only reason the article will give that Bach's authorship was challenged was that an unnamed somebody thought that the pieces didn't work well for the organ. Once another scholar pointed out that maybe they weren't written for the organ that apparently solved the entire problem. I have a hard time buying that. I'm going with Krebs' authorship not simply on instrumental grounds, but on stylistic grounds also.

Before I get to the stylistic grounds, though, I don't want to entirely gloss over the instrument argument. I've recently played several of Krebs' Chorale Preludes and noticed something. These pieces, all based on Lutheran Chorales, and presumably meant for the church, would, one might imagine, have been written for the organ. And yet they had no pedal parts at all. And they include rather un-organistic things like rolled chords and strange octave doublings, all things that apparently were noted when Bach's authorship of the "Eight" was challenged. Now Mr. Krebs, also according to Wikipedia, had trouble getting a church job for a while. Why does this matter? Because it makes it unlikely that he had regular access to an organ. If you don't have regular access to an organ, how effectively are you likely to write for one? And if you aren't connected to a church, it isn't likely that you are going to have an organ at home. Persons like Bach often had pedal harpsichords at home, but then, one's economic situation had to permit it. Even the "Eight" have very simple pedal parts. The a minor fugue contains only one pedal entrance toward the end. In the F major prelude, the pedal doubles the bass line, playing only the first beat of the bar. In the C major, the pedal nearly always moves with the other voices. In the fugue it shows independence, but the fugue is awfully short. This has always made the "Eight" useful for young organists who are still learning to use the pedals, but it makes it hard to mount an argument for Bach's authorship. Bach stuck out from other composers because he makes extensive use of the pedal. It is an integral part of his organ compositions, and it is one reason most of them are so difficult. Not to mention a more thorough working out of the material.

And that's the other thing. Whoever wrote these pieces kept the fugues pretty short. It's almost as if they were glad to get them over with. Bach seemingly loved the fugue. His fugues are generally pretty long and pretty involved. It just doesn't smell right.

Ok, he could, very occasionally, write a short fugue (the C# major in Book II of WTC, for instance). And it is possible that he was writing these pieces for a student, like one of his sons. But even there it seems odd. Even Bach's known student pieces, like the French Suites or the 2-part inventions, are pretty tricky stuff. These preludes and fugues are easier than those (particularly if you don't include pedal coordination issues), and they seem to be much less contrapuntally intricate than what Bach tended to write. Some of them, like the preludes in F major and g minor, mainly outline chords and behave in a much more style galant manner about them (which is basically accusing them of belonging to musical ideas that were in the air in the generation that came after Bach and that Bach resisted). Sure, there are the preludes in C and c minor (WTC I), but they explore harmony much more subtly, and delve into far more sophisticated regions than the I-IV-V/V-V kind of stuff you get in the F major prelude.

It isn't just pieces like the famous C Major prelude that show what kinds of harmonies Bach could come up with--the Piece d'Orgue has a nearly ridiculous ending where, over a very prolonged pedal note, Bach just keeps it up with harmony after harmony, on and on, thinking of one more and then one more and then one more. By contrast, the few chords that adorn pedal points in these works (and then mostly I and V) are quite pedestrian.

Maybe I'm being unfair by comparing these pieces to mature Bach. If I were trying to make a case for Bach's authorship of these pieces, I think I would place them quite early, alongside the Neumeister Chorales which Bach is said to have written as a teenager. These have less involved pedal, or no pedal, and are generally simpler to play. I don't know them very well; perhaps I should make a study of them and get back to you on this point.

In the end, though, it isn't merely the details that make me doubt that Bach wrote these pieces. It is the cumulative effect of these details. For instance, there are at least two pedal solos in the pieces, passages for the pedal alone, one in the G major and one in the Bb major prelude (I've only played 6 of them so far). While that seems to gainsay some of what I've said about the scant use of the pedal, these are still the only times the pedal has a very tricky or involved part--when it is playing completely alone, without commentary from the manuals. And the Bb prelude solo in particular, though it might pose some technical challenge, is pretty stiff. Repetitive, harmonically static, it sounds more like a pedal exercise than part of the musical argument. The Bb one reminds me of a paler version of the pedal solo in the Toccata Adagio and Fugue. Now a student of Bach might be expected to pick up some of the master's traits, namely a significant use of the pedal. But he would likely not be able to fully integrate that idea until much later, if at all.

A great many of these arguments, pro and con, cluster around one basic assumption. Just as I wrote when I discussed the possible Bach authorship of the famous Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, if one holds a high opinion of these pieces, one tends to assume they must have been written by the great Bach. If one is less enthusiastic about the pieces, it is easy to assign them to some lesser light of the Baroque era. I personally find them less appealing than I did as a youth. That was a time when the short, arresting ideas present in the A Minor Prelude were far more important to me than the working out (or lack) of those ideas, when the bounce and zest of the F major, and the ease of playing it, charmed, and the limited harmonic variation did not bother, when the rich sound of the C major prelude and the grave tone of the g minor seemed to capture something of my spirit in tones, and the awkwardness of construction did not give me pause. But as I've grown musically, the undeveloped totality of the pieces has come to my attention; I simply cannot appreciate them as much as I did in the days when the D Minor Toccata was interesting and the C Minor Passacaglia was too dense for me. Now it is the other way around: I understand and appreciate--no, love, many a piece written by a great composer later in life, when their craft was more fully developed. That is more likely to happen when a listener is also more fully developed. I still find these pieces charming, but they are not as they once were. Pity, I suppose, but then, a whole new musical ocean has opened up, much deeper than the shallow pool I left.

In order to give you some idea of what I mean, next week I'll offer several details about places in the "Eight" where I think Bach would have improved the music as it now stands, places that are testament to a composer who had some fine ideas and some charming means of working them out, but also stumbled occasionally. Either because the composer was not Bach, or was, as I've also suggested, a very young version of the eventual master, who would have learned from his own work as well as that of others, constantly improving his art, these items should give us some insight into what may separate a really fine composition from a merely good composition. The aim is not to denigrate the pieces, or to cast aspersions on Krebs, or whomever wrote them. The idea is to see what we can learn along the way in order to sharpen our own apprehension of the musical process. See you back here next week?

In the process, I wound up revisiting the "8 short preludes and fugues;" pieces that I hadn't played since I was a teenager, and then probably not well, and certainly not all of them, preludes and fugues together. I've gotten a whole lot more disciplined since then, with a better technical arsenal, and more time to spend at the organ as well. So it feels like at last I'm finishing something I started almost three decades ago, long before I learned to play the major Bach works of the past several years.

But this also brings with it a musicological question. Who wrote these pieces? When I first encountered them, at the age of 13, they were attributed (in my book) to J. S. Bach. I didn't know Bach's style very well, so I just went along with it. It was in a book, after all, so they must be right! Since then, I've changed my mind. Which is why, this weekend at church I'll play two of the pieces as part of my three week birthday celebration of Mr. Krebs. It would be a shame if I was celebrated the man's birthday with music he didn't actually write. But I'm pretty confident in my attribution.

Once I heard about the controversy, though, I wanted to find out about it. I'm pretty short on time these days, however, so all I've managed to do so far is go to Wikipedia. The article there was pretty biased in favor of Mr. Bach being the author. Why do I say that? Because all they will tell me is that there "used to be" "some" who thought that Krebs was the composer. Notice they don't name anybody. But now, they say, Bach is again thought to be the composer, and this time they list three scholars who are inclined to that opinion. [update: the article has undergone significant editing since this blog was written]

The only reason the article will give that Bach's authorship was challenged was that an unnamed somebody thought that the pieces didn't work well for the organ. Once another scholar pointed out that maybe they weren't written for the organ that apparently solved the entire problem. I have a hard time buying that. I'm going with Krebs' authorship not simply on instrumental grounds, but on stylistic grounds also.

Before I get to the stylistic grounds, though, I don't want to entirely gloss over the instrument argument. I've recently played several of Krebs' Chorale Preludes and noticed something. These pieces, all based on Lutheran Chorales, and presumably meant for the church, would, one might imagine, have been written for the organ. And yet they had no pedal parts at all. And they include rather un-organistic things like rolled chords and strange octave doublings, all things that apparently were noted when Bach's authorship of the "Eight" was challenged. Now Mr. Krebs, also according to Wikipedia, had trouble getting a church job for a while. Why does this matter? Because it makes it unlikely that he had regular access to an organ. If you don't have regular access to an organ, how effectively are you likely to write for one? And if you aren't connected to a church, it isn't likely that you are going to have an organ at home. Persons like Bach often had pedal harpsichords at home, but then, one's economic situation had to permit it. Even the "Eight" have very simple pedal parts. The a minor fugue contains only one pedal entrance toward the end. In the F major prelude, the pedal doubles the bass line, playing only the first beat of the bar. In the C major, the pedal nearly always moves with the other voices. In the fugue it shows independence, but the fugue is awfully short. This has always made the "Eight" useful for young organists who are still learning to use the pedals, but it makes it hard to mount an argument for Bach's authorship. Bach stuck out from other composers because he makes extensive use of the pedal. It is an integral part of his organ compositions, and it is one reason most of them are so difficult. Not to mention a more thorough working out of the material.

And that's the other thing. Whoever wrote these pieces kept the fugues pretty short. It's almost as if they were glad to get them over with. Bach seemingly loved the fugue. His fugues are generally pretty long and pretty involved. It just doesn't smell right.

Ok, he could, very occasionally, write a short fugue (the C# major in Book II of WTC, for instance). And it is possible that he was writing these pieces for a student, like one of his sons. But even there it seems odd. Even Bach's known student pieces, like the French Suites or the 2-part inventions, are pretty tricky stuff. These preludes and fugues are easier than those (particularly if you don't include pedal coordination issues), and they seem to be much less contrapuntally intricate than what Bach tended to write. Some of them, like the preludes in F major and g minor, mainly outline chords and behave in a much more style galant manner about them (which is basically accusing them of belonging to musical ideas that were in the air in the generation that came after Bach and that Bach resisted). Sure, there are the preludes in C and c minor (WTC I), but they explore harmony much more subtly, and delve into far more sophisticated regions than the I-IV-V/V-V kind of stuff you get in the F major prelude.

It isn't just pieces like the famous C Major prelude that show what kinds of harmonies Bach could come up with--the Piece d'Orgue has a nearly ridiculous ending where, over a very prolonged pedal note, Bach just keeps it up with harmony after harmony, on and on, thinking of one more and then one more and then one more. By contrast, the few chords that adorn pedal points in these works (and then mostly I and V) are quite pedestrian.

Maybe I'm being unfair by comparing these pieces to mature Bach. If I were trying to make a case for Bach's authorship of these pieces, I think I would place them quite early, alongside the Neumeister Chorales which Bach is said to have written as a teenager. These have less involved pedal, or no pedal, and are generally simpler to play. I don't know them very well; perhaps I should make a study of them and get back to you on this point.

In the end, though, it isn't merely the details that make me doubt that Bach wrote these pieces. It is the cumulative effect of these details. For instance, there are at least two pedal solos in the pieces, passages for the pedal alone, one in the G major and one in the Bb major prelude (I've only played 6 of them so far). While that seems to gainsay some of what I've said about the scant use of the pedal, these are still the only times the pedal has a very tricky or involved part--when it is playing completely alone, without commentary from the manuals. And the Bb prelude solo in particular, though it might pose some technical challenge, is pretty stiff. Repetitive, harmonically static, it sounds more like a pedal exercise than part of the musical argument. The Bb one reminds me of a paler version of the pedal solo in the Toccata Adagio and Fugue. Now a student of Bach might be expected to pick up some of the master's traits, namely a significant use of the pedal. But he would likely not be able to fully integrate that idea until much later, if at all.

A great many of these arguments, pro and con, cluster around one basic assumption. Just as I wrote when I discussed the possible Bach authorship of the famous Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, if one holds a high opinion of these pieces, one tends to assume they must have been written by the great Bach. If one is less enthusiastic about the pieces, it is easy to assign them to some lesser light of the Baroque era. I personally find them less appealing than I did as a youth. That was a time when the short, arresting ideas present in the A Minor Prelude were far more important to me than the working out (or lack) of those ideas, when the bounce and zest of the F major, and the ease of playing it, charmed, and the limited harmonic variation did not bother, when the rich sound of the C major prelude and the grave tone of the g minor seemed to capture something of my spirit in tones, and the awkwardness of construction did not give me pause. But as I've grown musically, the undeveloped totality of the pieces has come to my attention; I simply cannot appreciate them as much as I did in the days when the D Minor Toccata was interesting and the C Minor Passacaglia was too dense for me. Now it is the other way around: I understand and appreciate--no, love, many a piece written by a great composer later in life, when their craft was more fully developed. That is more likely to happen when a listener is also more fully developed. I still find these pieces charming, but they are not as they once were. Pity, I suppose, but then, a whole new musical ocean has opened up, much deeper than the shallow pool I left.

In order to give you some idea of what I mean, next week I'll offer several details about places in the "Eight" where I think Bach would have improved the music as it now stands, places that are testament to a composer who had some fine ideas and some charming means of working them out, but also stumbled occasionally. Either because the composer was not Bach, or was, as I've also suggested, a very young version of the eventual master, who would have learned from his own work as well as that of others, constantly improving his art, these items should give us some insight into what may separate a really fine composition from a merely good composition. The aim is not to denigrate the pieces, or to cast aspersions on Krebs, or whomever wrote them. The idea is to see what we can learn along the way in order to sharpen our own apprehension of the musical process. See you back here next week?

Friday, October 18, 2013

Serving two Masters

I was a little off yesterday. Can you tell?

[listen]

I hope not. Despite feeling a little peckish and having fingers that weren't quite as articulate as I would have liked, I like to think that they were trained enough to get down to business, suck it up, and do what needed to be done when it counted. Ten fingers, go! (and you feet, too).

By the way, that little piece was the first of a collection known to organists as the "8 Little Preludes and Fugues" and was once thought to have been written by J. S. Bach. Actually, depending on who you talk to it still is thought to be by Bach. But I'll get into that issue in next week.

I made this recording as a sort of "break" from learning a contemporary trumpet sonata. It's called "The Mysteries Remain" and is 28 pages of largely non-tonal writing, which requires me to essentially familiarize myself with all sorts of unusual clusters of notes, angular melodic cells, and so on. In a few days the piece will start to come around, and hopefully sound like music, but early this week it was making my head hurt so after a few days of kicking it around for four hours a day, and working on nothing else, I thought I'd take a break and do something simple and tonal.

It's my fault, really, for waiting too long to get started on a piece that I have to play in concert in exactly a month, busy schedule that I've had notwithstanding, and cramming the whole thing into my head in a few days had a predictable effect. But like I said, that should pay off by next week when I start rehearsing with the trumpet player. In the meanwhile I'm feeling rather worn out, mind and body. But then, I still managed to get the job done, and also to make a nice recording of another piece I had barely practiced. On a break. For stress relief. Not so bad, really.

I'm not trying to brag, especially if you are a person for whom learning a piece like the Prelude and Fugue in C and playing it for a recording is a major achievement. Sure, I learned and recorded it in about a day, but to start with, I've logged at least 10,000 hours of practice over my lifetime and spent over twelve years at music school just learning how to perform. And I still spend a large part of my day practicing. Besides a general reservoir of skill built up over years of patient labor, the reason I can even do things like that are that I've been dealing in large quantities of music on short deadlines for quite some time. I've acquired skills relating to preparing music well an in a hurry, and I've also learned to plan far ahead whenever possible, so that, in this case, the things I'm playing in church this month are already learned (they were easy) so I can focus all week on something I'm playing for a concert instead.

That doesn't mean there aren't conflicts. I've got three concerts coming up this remaining calendar year, with three programs of varying lengths, and, of course, about a dozen Sunday services to prepare for over that same stretch. That's a lot of music.

"Jesus said, "no one can serve two masters. Either he will hate one and love the other, or love the one and despise the other."

Then there is the old question about how much one musically "gives" to the church. Since I spent pretty much the whole week working on concert repertoire (my other "break" was to learn another piece to play on one of the other concerts, tonal, and easier on the mind, if not the fingers) that issue is on my mind today. My experience has been that quite often musicians spend most of their time preparing for concerts and other secular events, and then throwing stuff together on Sunday morning. It is a major reason that, as I suggested two weeks ago, most people don't expect a lot of quality out of their church music.

My experience may be anecdotal, but I can think of several historical examples as well. There is J. S. Bach, of course, who wrote a great deal of glorious, and difficult, instrumental (and choral) music for the church, at least half of his output, and clearly spent a lot of time at it. But there is his contemporary, Georg Telemann, who, as prolific as he was, dashed off a few short pieces for the organ and that's about it (instrumentally). They are charming, and well written, but it is pretty clear he wasn't really all that into church music. He'd decided, I suspect, that the way to advance a career and make a name was in the theater and the concert hall.

Other folks, like Mozart, who paid lip service to the organ but never wrote anything at all for it, or Gabriel Faure, who spent his entire like as a church organist and didn't write anything for his instrument, remind us of the bargain that often is struck. Sure, I work in a church, but that's not really where I put in my time. It's just a job.

That isn't my style. Sure, this entire month I'm playing easy literature, celebrating the 300th birthday of an obscure Bach student while simultaneously clearing time from my schedule to do other things, but I am planning to play well, putting in enough time and planning ahead. There is a big difference between simple done poorly and simple done well. I've heard enough organists clearly sight reading on Sunday morning, stumbling over passages and missing notes, organists with advanced degrees and plenty of experience who play much better than that on their organ recitals and in concerts, to know that.

The professional solution to all this is, ironically, to sound just as good when you haven't had much practice as you do when you are on full strength. Be consistent. Obviously practice time means something, but if you can really bring your A game under any circumstances you and everyone else are better off. And this is exactly what service in a church requires anyhow. There is never enough time to prepare everything. And next week is right around the corner. I think I once counted some 40 musical items I play in four church services every weekend. Some I have to sight read or play on only one short rehearsal. It's ironic that you have to prepare to learn how to not be able to prepare, but that's the long and short of it. Being able to handle more than you can handle and still managing to sound like you can handle it.

Which reminds me of something else Jesus said. Remember the parable with the three servants, two of whom invest their master's money when he goes away and a third who does not? The first two double their money and receive a commendation from the master when he returns, and...guess what. More work! "You have been faithful in a few things," he says, "now I'll put you in charge of more."

Is that really a happy ending? Talk about overload! But anybody who serves musically in a church knows how that works, don't they?

Which is why you have to be able to sight read like crazy. To play your own part with no discernible errors in it so that you can spend all your time focusing on the people you are playing with. To be able to help them with a well chosen note or two when they need it. To communicate quickly and effectively how you are going to start/stop/play the piece and also not to worry if they skip a beat because you can catch them and keep the music going without a hitch. And you will catch them, right? Adding a beat or two to a score at random is a must for a church musician. That, along with learning how to go on with no warning, no planning, no warm up time, and barely any concentration on your own thing because you have to concentrate on their thing--the complete opposite of all the things I would suggest contribute to quality--that is just what you have to do. Week after week. It's quite a challenge. If you want it to be, of course. If you accept the challenge, and try to figure out how to actually make all that impossible stuff work out well. You get 52 tries a year, if not more.

How do you learn all this? Just by doing it, week after week, with your ear to the ground, and making notes to yourself how to get better every day. And reading this blog, of course. :)

Because, on a tight schedule like ours, there is really no time for learning, there is only time for doing it well. And yet, simultaneously, there is all the time in the world.

[listen]

I hope not. Despite feeling a little peckish and having fingers that weren't quite as articulate as I would have liked, I like to think that they were trained enough to get down to business, suck it up, and do what needed to be done when it counted. Ten fingers, go! (and you feet, too).

By the way, that little piece was the first of a collection known to organists as the "8 Little Preludes and Fugues" and was once thought to have been written by J. S. Bach. Actually, depending on who you talk to it still is thought to be by Bach. But I'll get into that issue in next week.

I made this recording as a sort of "break" from learning a contemporary trumpet sonata. It's called "The Mysteries Remain" and is 28 pages of largely non-tonal writing, which requires me to essentially familiarize myself with all sorts of unusual clusters of notes, angular melodic cells, and so on. In a few days the piece will start to come around, and hopefully sound like music, but early this week it was making my head hurt so after a few days of kicking it around for four hours a day, and working on nothing else, I thought I'd take a break and do something simple and tonal.

It's my fault, really, for waiting too long to get started on a piece that I have to play in concert in exactly a month, busy schedule that I've had notwithstanding, and cramming the whole thing into my head in a few days had a predictable effect. But like I said, that should pay off by next week when I start rehearsing with the trumpet player. In the meanwhile I'm feeling rather worn out, mind and body. But then, I still managed to get the job done, and also to make a nice recording of another piece I had barely practiced. On a break. For stress relief. Not so bad, really.

I'm not trying to brag, especially if you are a person for whom learning a piece like the Prelude and Fugue in C and playing it for a recording is a major achievement. Sure, I learned and recorded it in about a day, but to start with, I've logged at least 10,000 hours of practice over my lifetime and spent over twelve years at music school just learning how to perform. And I still spend a large part of my day practicing. Besides a general reservoir of skill built up over years of patient labor, the reason I can even do things like that are that I've been dealing in large quantities of music on short deadlines for quite some time. I've acquired skills relating to preparing music well an in a hurry, and I've also learned to plan far ahead whenever possible, so that, in this case, the things I'm playing in church this month are already learned (they were easy) so I can focus all week on something I'm playing for a concert instead.

That doesn't mean there aren't conflicts. I've got three concerts coming up this remaining calendar year, with three programs of varying lengths, and, of course, about a dozen Sunday services to prepare for over that same stretch. That's a lot of music.

"Jesus said, "no one can serve two masters. Either he will hate one and love the other, or love the one and despise the other."

Then there is the old question about how much one musically "gives" to the church. Since I spent pretty much the whole week working on concert repertoire (my other "break" was to learn another piece to play on one of the other concerts, tonal, and easier on the mind, if not the fingers) that issue is on my mind today. My experience has been that quite often musicians spend most of their time preparing for concerts and other secular events, and then throwing stuff together on Sunday morning. It is a major reason that, as I suggested two weeks ago, most people don't expect a lot of quality out of their church music.

My experience may be anecdotal, but I can think of several historical examples as well. There is J. S. Bach, of course, who wrote a great deal of glorious, and difficult, instrumental (and choral) music for the church, at least half of his output, and clearly spent a lot of time at it. But there is his contemporary, Georg Telemann, who, as prolific as he was, dashed off a few short pieces for the organ and that's about it (instrumentally). They are charming, and well written, but it is pretty clear he wasn't really all that into church music. He'd decided, I suspect, that the way to advance a career and make a name was in the theater and the concert hall.

Other folks, like Mozart, who paid lip service to the organ but never wrote anything at all for it, or Gabriel Faure, who spent his entire like as a church organist and didn't write anything for his instrument, remind us of the bargain that often is struck. Sure, I work in a church, but that's not really where I put in my time. It's just a job.

That isn't my style. Sure, this entire month I'm playing easy literature, celebrating the 300th birthday of an obscure Bach student while simultaneously clearing time from my schedule to do other things, but I am planning to play well, putting in enough time and planning ahead. There is a big difference between simple done poorly and simple done well. I've heard enough organists clearly sight reading on Sunday morning, stumbling over passages and missing notes, organists with advanced degrees and plenty of experience who play much better than that on their organ recitals and in concerts, to know that.